An E-2 investor discovers they can return to the U.S. despite a 10-year immigration bar, marries a U.S. citizen, then wonders: can they get a green card without leaving again? The answer is yes, but it requires careful strategy.

For individuals with prior immigration violations—especially those who have triggered the 10-year unlawful presence bar under INA §212(a)(9)(B)(i)(II)—the path to permanent residency can appear closed. Yet, in certain cases, individuals lawfully re-enter the U.S. on a nonimmigrant visa with a §212(d)(3) waiver and later marry a U.S. citizen, raising the question: Can they now adjust status, and if so, how?”

This article outlines how this situation arises, why it’s rare but legally sound, and how best to navigate the adjustment process given the active 10-year bar.

I. How This Scenario Arises: A Rare But Viable Path

It’s relatively uncommon for someone subject to a 10-year bar for unlawful presence to receive a §212(d)(3) nonimmigrant waiver and be allowed back into the U.S. The statute provides broad discretionary authority to waive most grounds of inadmissibility for temporary (nonimmigrant) entries. However, U.S. consulates and CBP officers apply this authority sparingly.

In practice, the waiver is most often granted when the U.S. has an interest in the applicant’s presence, especially in the context of business investment, international trade, or diplomatic policy. A common example is an E-2 investor from a treaty country who:

- Previously overstayed a visa (triggering the 10-year bar),

- Departed the U.S. and applied for a new E-2 visa,

- Presented a compelling case (e.g., business employs U.S. workers, has substantial investment),

- Was granted a 212(d)(3) waiver by the consulate in conjunction with the E visa.

The U.S. benefits economically or politically from their presence, tipping the discretionary balance in their favor.

This lawful admission creates the conditions for adjustment of status under INA §245(a)—but the underlying inadmissibility due to unlawful presence remains unresolved.

II. Legal Background: The Limits of 212(d)(3)

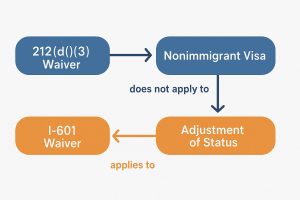

A §212(d)(3) waiver is temporary and nonimmigrant in scope. It does not “cure” the inadmissibility for immigrant purposes. While it permits lawful admission for a nonimmigrant stay, it does not forgive the underlying bar for purposes of obtaining a green card.

Therefore, an individual in this position, even if lawfully present under an E-2 or B-1/B-2 visa, is still inadmissible for adjustment of status under INA §212(a)(9)(B) unless:

- They have remained outside the U.S. for 10 years since the triggering event (not the case here), or

- They receive an immigrant waiver under Form I-601.

III. The Solution: I-601 Waiver Strategy for Adjustment of Status

- When the applicant marries a U.S. citizen and seeks to adjust status under INA §245(a), USCIS must examine all applicable grounds of inadmissibility. Since the applicant triggered the 10-year bar by accruing >1 year of unlawful presence and departing, they are inadmissible under 212(a)(9)(B)(i)(II).

In this scenario, they must file a Form I-601 waiver with their AOS application to overcome the inadmissibility.

The waiver requires:

- A qualifying relative (in this case, the U.S. citizen spouse),

- A showing of extreme hardship to that spouse if the applicant is denied admission.

Evidence may include medical, financial, psychological, and country condition documentation, among other factors.

IV. Strategic Timing: When Should the Waiver Be Filed?

A common strategic question arises: Should the I-601 waiver be filed with the adjustment application, or only after USCIS requests it?

Parallel Filing: When Waiver Is Clearly Needed

In cases like the one described here, the inadmissibility ground is clear and unambiguous: the 10-year bar applies, and the individual has not yet satisfied it by remaining outside the U.S.

In such cases:

- There is no ambiguity about whether a waiver will be required.

- Filing I-601 concurrently with the I-485 avoids delay.

- The waiver is adjudicated in parallel with the adjustment application, potentially shaving months off the overall processing time.

- The applicant becomes a lawful permanent resident sooner if the waiver is granted.

This approach is especially appropriate when the applicant and attorney agree that the legal and factual record guarantees a finding of inadmissibility, and there is no reasonable prospect of avoiding the need for a waiver.

Deferred Filing: When Waiver Need Is Unclear

On the other hand, if there’s some question as to whether the applicant is inadmissible, deferring the waiver may be the prudent course. For example:

- If the client was a minor during the unlawful presence period,

- If the period of unlawful presence was ambiguous (e.g., D/S notation),

- If the 10-year bar may have already expired due to time spent outside the U.S

In those cases, it is often wise to wait until USCIS issues a Request for Evidence (RFE) or Notice of Intent to Deny (NOID) before filing Form I-601. This approach:

- Saves time and resources if no waiver is ultimately required,

- Allows a more focused waiver submission tailored to USCIS’s specific findings.

But in cases involving a confirmed 10-year bar and lawful nonimmigrant entry with a 212(d)(3) waiver, filing the I-601 at the outset is usually the better strategy.

V. Practical Filing Structure

An optimized adjustment package in this scenario typically includes:

- Form I-130, filed by the U.S. citizen spouse

- Form I-485, application for adjustment of status

- Form I-765 and I-131, for work and travel authorization (if needed)

- Form I-601, waiver of inadmissibility

- Waiver package, including:

- Legal brief explaining the inadmissibility and waiver eligibility

- Documentary evidence of extreme hardship to the U.S. citizen spouse

- Immigration history, including prior unlawful presence and lawful readmission

- Evidence of lawful current status (e.g., E-2 entry)

This approach allows all components to be reviewed together and avoids serial adjudications, which cause delay.

VI. Final Considerations and Warnings

While this path is legally sound, a few cautionary notes:

- If the applicant previously reentered without inspection after triggering the 10-year bar, they may be subject to the permanent bar under INA §212(a)(9)(C), which cannot be waived from inside the U.S.

- If there was a prior removal order, an I-212 (permission to reapply) may also be required.

- If there is a misrepresentation or fraud finding, that too requires a separate waiver (also on Form I-601).

- No criminal history or additional grounds of inadmissibility should be assumed; every case requires full vetting of the facts.

Need Help With a Complex Adjustment Case? Cases involving 212(d)(3) waivers and concurrent I-601 applications require careful legal analysis and strategic timing. If you’re navigating adjustment of status with an active 10-year bar, contact our office for a consultation to evaluate your specific situation and develop the most effective approach.

Conclusion

Adjustment of status from within the U.S. following admission with a 212(d)(3) waiver is possible, but must be carefully structured. The key is recognizing that the underlying inadmissibility persists despite lawful admission and must be affirmatively waived using Form I-601. Where the 10-year bar is clearly in effect, it is typically advantageous to file the waiver alongside the adjustment application to avoid delay and reach lawful permanent residency sooner.

For clients with investment-based nonimmigrant status, this path may be not only viable but also strategically wise — provided the waiver is approached with a clear legal theory, detailed factual support, and realistic assessment of hardship.